The illegal, unprovoked, full-scale US-UK invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003 wrecked the country at the cost of at least one million Iraqi lives. It was waged on the basis of a supposed threat from ‘weapons of mass destruction’ that did not exist. Less well-known is the fact that everyone at the pinnacle of power knew they did not exist. The whole focus on Iraq as some kind of menace was an audacious fabrication. But ‘we’ got the oil.

As the war and occupation continued in 2006, prime minister Tony Blair was asked if he had ‘prayed to God’ over his involvement in the war. He replied: ‘Yes’, adding:

‘In the end, there is a judgement that, I think if you have faith about these things, you realise that judgement is made by other people… and if you believe in God, it’s made by God as well.’

US president, George W. Bush, Blair’s co-conspirator, also a Christian, said:

‘I’m driven with a mission from God. God would tell me, “George, go and fight those terrorists in Afghanistan.” And I did, and then God would tell me, “George go and end the tyranny in Iraq,” and I did.’

Rose Gentle, whose son Gordon died while serving with the Royal Highland Fusiliers in Iraq in 2004, commented:

‘A good Christian wouldn’t be for this war. I’m actually quite disgusted by the comments. It’s a joke.’

That would certainly have been the view of Leo Tolstoy who tore down centuries of hypocrisy in a single sentence:

‘A Christian nation which engages in war ought, in order to be logical, not only take down the cross from its church steeples, turn the churches to some other use, give the clergy other duties, having first prohibited the teaching of the Gospel, but also ought to abandon all the requirements of morality which flow from Christian law.’ (Tolstoy, ‘Writings on Civil Disobedience and Non-Violence’, New Society, 1987, p.xiv)

Tolstoy’s argument was simple:

‘You are told in the Gospel that one should not only refrain from killing his brothers, but should not do that which leads to murder: one should not be angry with one’s brothers, nor hate one’s enemies, but love them.

‘In the law of Moses you are distinctly told, “Thou shalt not kill,” without any reservations as to whom you can and whom you cannot kill.’ (pp.40-41)

And Jesus, of course, said:

‘Resist not evil.’

More elaborately, he said:

‘You have heard that it was said, “Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth.” But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also. And if someone wants to sue you and take your tunic, let him have your cloak as well. If someone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.’

Resist not the US-UK invasion of Iraq? Resist not the Israeli genocide in Gaza? Resist not the Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023? Resist not the fossil fuel industry’s subordination of people and planet to profit collapsing the climate and our prospects for survival?

Really? Is this to be taken seriously? What could have been meant by these words? Were they really intended as political counsel?

As we all know, in an attempt to make sense of them, the comments have been interpreted as advocacy for a righteous display of moral superiority: we ‘turn the other cheek’ to show how far above such primitive, face-slapping behaviour we are – we pointedly refuse to lower ourselves by replying in kind. The idea is that by offering another free hit we are delivering a lesson in dignity and self-control to someone lacking in both.

The common-sense understanding is that the willingness to suffer for our faith will have a sobering, Gandhian impact on our cheek-slapper – they will be impressed, elevated by our response. Thus, the world becomes a better place. We assume that this is what was intended, because how else can we make sense of the idea that we should not resist ‘Evil’? The problem with the argument is that it clearly involves an effort to resist ‘Evil’ by righteous example.

‘But Colonel, Shooting’s No Good!’

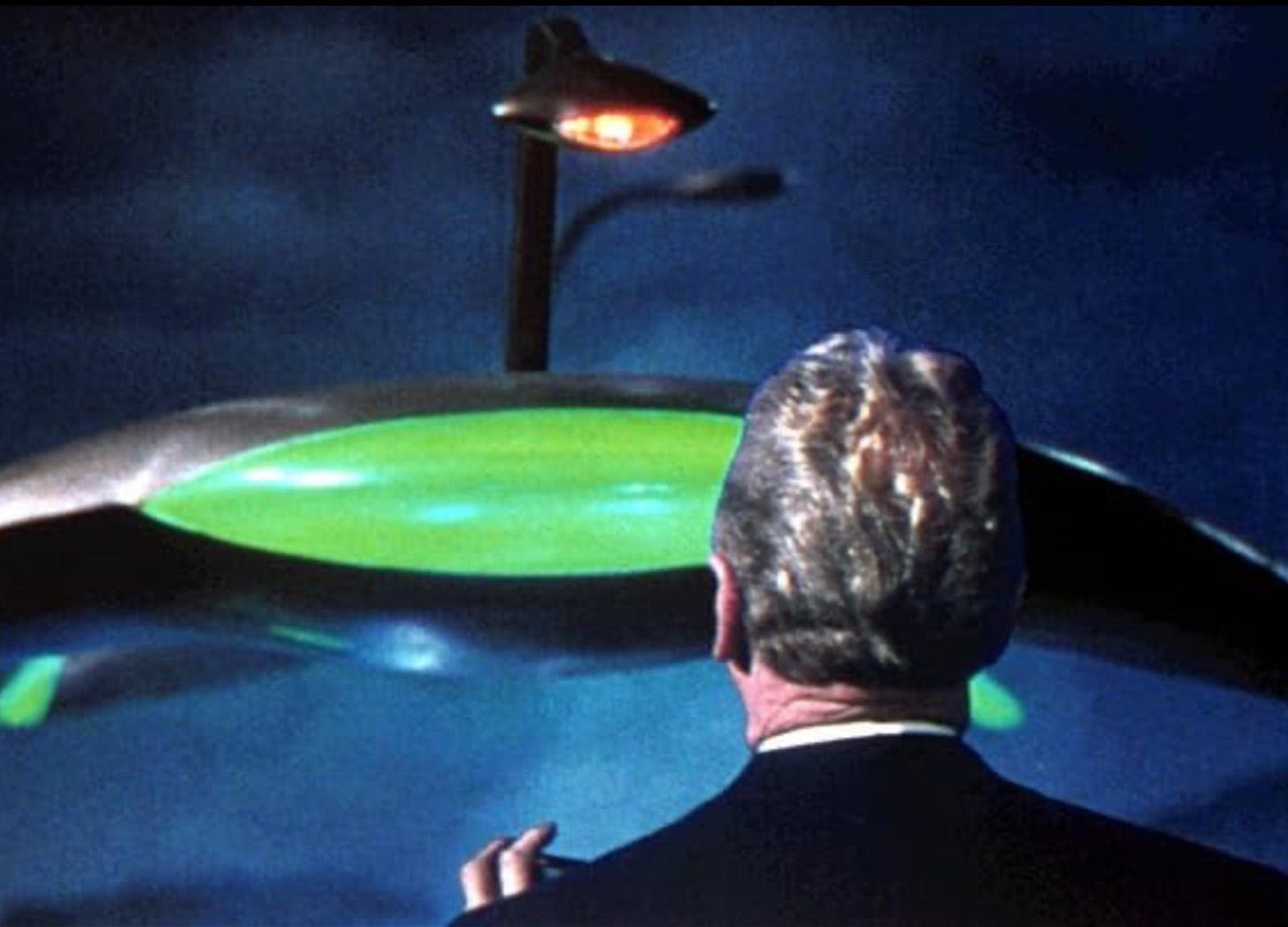

We think we know only too well where the determination to ‘turn the other cheek’ leads from the fate suffered by the Reverend Doctor Matthew Collins in the classic 1953 film version of ‘The War of the Worlds’. Though Martian invaders have already incinerated numerous Earthlings and are clearly bent on mayhem, Reverend Collins decides to wage peace on US Army Colonel Heffner stood in his bunker preparing to blast the aliens back to whatever hell they came from:

‘But Colonel, shooting’s no good!’

‘It’s always been a good persuader.’

‘Shouldn’t you try to communicate with them first, and shoot if you have to?’

The Colonel regards Collins with a mixture of bewilderment and contempt – he never saw a Martian yet that didn’t understand a good slap in the mouth or a slug from a .45 – and does not deign to reply.

Getting nowhere with the Colonel, employing the priestly intonation with which we are all so familiar, the Reverend turns to his niece, Sylvia:

‘I think we should try to make them understand we mean them no harm. They are living creatures out there. If they’re more advanced than us, they should be nearer the Creator for that reason. No real attempt has been made to communicate with them, you know.’

At this point, Collins decides to take matters into his own hands. Leaving the safety of the bunker, Bible held aloft, he strides boldly in the direction of the Martian warships. It is an ancient film now, but this remains a deeply affecting moment: the Man of God, alone, unarmed, literally staking his life on his faith. He is quickly detected by an alien machine, which turns a pulsing, serpentine heat-ray weapon in his direction, as he walks on and intones:

‘Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil. Thou anointest my head with oil. My cup runneth over. And I will dwell in the house of the Lord… forever.’

As this last word is spoken, with great brutality: a blazing ejaculation of fire. Collins is incinerated. Dead. ‘Forever’.

Back in the bunker, the Colonel’s response:

‘LET ‘EM HAVE IT!’

Tanks, guns, rockets and mortars unleash a barrage of counter-fire.

The answer is in, and it is emphatic: Jesus was wrong! Reverend Collins was wrong! The Colonel and everyone like him – including us, most of us – are right: if you don’t resist ‘Evil’, if you attempt to placate ‘Evil’, if you try to reason with ‘Evil’, you will be annihilated. When fantasy meets the real world, fantasy is vaporised. And such has been and always will be the case, every time – ‘forever’.

It was just a film, albeit a highly successful one, but it had an immense impact on its audience. It certainly had an impact on me. The torrent of alien fire, and the military response, have the authority of Truth. What happens to the Reverend seems brutal, terrible. But the fire is cleansing, beautiful in a way; it burns away all childish dreaming.

In H.G. Wells’s original novel, and in the film, humble bacteria succeed in defeating the invaders where military force fails. It is certainly suggested that we might thank ‘The Creator’ for that. But the clear message, certainly of the film, is that ‘Evil’ must be resisted.

Crowded Sofas

And so, we have been resisting ‘Evil’, or claim to have been resisting ‘Evil’. Or we have believed that the only answer to ‘Evil’ – howsoever defined – is resistance.

‘Mainstream’ politicians and press have been resisting the ‘Evil’ of various Official Enemies – the Soviets, the Vietnamese, the Chinese, Milosevic, Saddam Hussein, Bin Laden, Gaddafi, Assad, Putin… on and on. We are always Colonel Heffner and Reverend Collins facing an alien threat, and we are always told we have a choice to make between deluded, suicidal appeasement and ultra-violence; between fantasy and reality. Meanwhile, the progressive left has been resisting capitalism, corporate psychopathy, state warmongering for resources, and so on…

Even in our private lives, we know that millions of Reverend Collinses and Colonel Heffners are sitting beside millions of mini-me Hitlers on sofas (quite a threesome!). Here, also, we can choose idealistic, happy-clappy appeasement; or we can resist injustice and tyrannical abuse. We can demand that they also put their dishes in the machine; that they also clean the bath properly with that blue stuff and the fish-shaped sponge; that they also throw the rubbish from time to time. Who made us The Garbage Person?!

Or we can sit back, Bible aloft, and watch our happiness being trashed by escalating, limitless narcissism:

‘“Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…”? No! You walk through the valley of the shadow of the shopping centre and get the groceries like I did yesterday!’

‘No real attempt has been made to communicate about this issue, you know.’

‘No, because it’s YOUR TURN!’

Well, it’s quite right, isn’t it? Like Barack Obama, we need ‘red lines’, boundaries. Like George Bush Senior we have to declare that ‘This will not stand!’ Order depends on us not letting ourselves be walked over. We have to resist the domestic version of, well, ‘Evil’.

And yet, and yet… despite all of this endlessly principled resistance, the world is full…. nay, flooded, with what looks an awful lot like ‘Evil’.

Everywhere we turn: ludicrously unsustainable over-consumption as if the next year and the next generation didn’t matter a damn; a factory farming system creating hell on earth for animals; a seething mass of military-industrial complexity gorged on war; manifestly fake political choices that are no-choice serving the same money-grubbing interests; fossil fuel fanaticism subordinating literally everyone – even, ultimately, the CEOs and their own families – to short-term profit; levers of power controlling economics and war absolutely cordoned off from public participation. Oh, we can talk the talk on social media all we like, but don’t even think about laying a finger on the levers of power. It’s a complicated game, and that outcome is not in the rules.

Noam Chomsky commented that he could not find a word to describe the climate-trashing fossil fuel interests willing to sacrifice the literal existence of organised human life for the sake of a few dollars more:

‘The word “evil” doesn’t begin to approach it.’

And… it feels almost incredible even to write it… almost no-one is doing anything meaningful about it!

The irony is exquisite – after decades, centuries, millennia of focusing on the need to resist ‘Evil’, almost nobody – certainly nobody with power – is seriously trying to resist the ultimate ‘Evil’ of human self-extinction. We are trapped in an airliner heading straight for a mountain and there is no-one in the cockpit who cares.

The effort to resist ‘Evil’ appears to have failed. And that suggests that we might like to take another look at Jesus’s advice. Perhaps we misunderstood him. Perhaps it is not him, but the likes of Reverend Collins – and all of us who assumed that people like Collins had interpreted Jesus correctly – who are naive. Perhaps something quite different was intended.

Part 2 will follow shortly…

David Edwards is co-editor of medialens.org and author of the forthcoming, ‘A Short Book About Ego… and the Remedy of Meditation’, Mantra Books, 24 June 2025, available here. The e-book will be available imminently. Email: davidmedialens@gmail.com

Intriguing... I look forward to part 2. You're probably familiar with Orwell's reflections on Gandhi (which may in themselves place a bit too much faith in the power of the press and mass protests):

"It is difficult to see how Gandhi’s methods could be applied in a country where opponents of the regime disappear in the middle of the night and are never heard of again. Without a free press and the right of assembly, it is impossible not merely to appeal to outside opinion, but to bring a mass movement into being, or even to make your intentions known to your adversary. Is there a Gandhi in Russia at this moment? And if there is, what is he accomplishing? The Russian masses could only practise civil disobedience if the same idea happened to occur to all of them simultaneously, and even then, to judge by the history of the Ukraine famine, it would make no difference. But let it be granted that non-violent resistance can be effective against one’s own government, or against an occupying power: even so, how does one put it into practice internationally? Gandhi’s various conflicting statements on the late war seem to show that he felt the difficulty of this. Applied to foreign politics, pacifism either stops being pacifist or becomes appeasement. Moreover the assumption, which served Gandhi so well in dealing with individuals, that all human beings are more or less approachable and will respond to a generous gesture, needs to be seriously questioned. It is not necessarily true, for example, when you are dealing with lunatics. Then the question becomes: Who is sane? Was Hitler sane? And is it not possible for one whole culture to be insane by the standards of another? And, so far as one can gauge the feelings of whole nations, is there any apparent connection between a generous deed and a friendly response? Is gratitude a factor in international politics?"

https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/reflections-on-gandhi/